DECATHLON works with collectors/sorters (organisations that collect and sort by colour, material, etc.).

We buy these raw materials and then send them to recyclers. It is they who turn this stock of used clothes into new cotton fibres. Today, we favour mechanical recycling (the fabric is shredded, frayed and does not undergo chemical treatment, as in a 'classic' spinning process) to recycle these fibres.

The other advantage is that this technique does not denature the fibre: it retains the virtues of virgin cotton (such as its feel and appearance). The disadvantage, because it has to be admitted that there could be some, is that the question of quality has to be asked differently. With this technique, the fibres are slightly shorter, which reduces quality (a reduction that translates into less resistance or the risk of pilling). To avoid this risk, we need to strike a balance between recycled cotton and virgin cotton. We find this balance of 30% (recycled) / 70% (virgin), to maintain a good level of quality. (nb: At the end of the life of this "mixed product", another recycling loop could be envisaged. That said, yes, mechanically, each potential recycling will reduce the length of the fibre and, therefore, the quality).

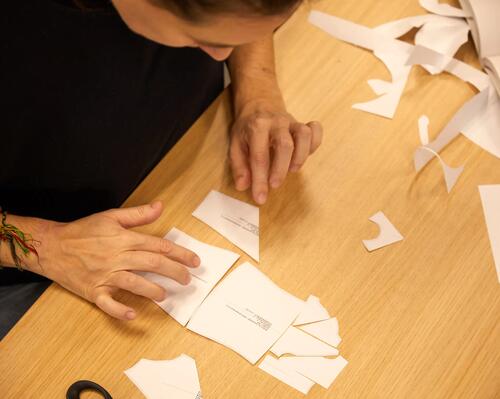

The other point is contamination. Yes, it can be a bit frightening, but the word “contamination” reflects a very simple and not very frightening reality: when using fabrics from collections, we sometimes find small irregularities: a light yellow thread that could have slipped into batches of white fabrics, for example. The quality and strength of the new fibres would obviously not be called into question, but some people might regard this as a visual defect. But that's what makes a t-shirt (for example) unique, and still carries with it a small part of its former life, made up this time of little journeys! Because here, there's no question of flying around the world: the collection takes place in Europe, the yarn is processed in Spain or Portugal, the knitting, finishing, and tailoring in Egypt and the supply area and market remain in this zone (for the moment, in 2023, this process is banned in China and India also works on a local to local basis).

Finally, the other challenge posed by this new process has to do with the law: how can the composition labels be filled in directly if we don't know exactly where the recycled clothes come from? How do you manage any chemical risks? Persistent traces of products that were previously authorized but are no longer? These are questions that manufacturers are working on.